The role of a national cancer registry in effective implementation and monitoring of the Global Breast Cancer Initiative (GBCI) framework in Ghana: a narrative review

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most diagnosed cancer among females in the world, with 2.3 million new cases diagnosed and a mortality rate of over 666,000 persons annually (1). West Africa accounts for 27% of all breast cancer cases diagnosed in the African continent and 30.6% of breast cancer mortality in Africa (2). Breast cancer is fundamentally an economic and social issue because the lives of women who work and contribute financially to countries and who are sometimes the bread winners of their families are cut short by a disease that is treatable and curable when detected early. In 2020, 120 children became maternal orphans every hour, of whom 25% lived in Africa. Further, 45% of all maternal orphans are caused by breast and cervical cancers; the two most diagnosed cancers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) today (3). In Sub-Saharan Africa, 121 maternal orphans are created for every 100 deaths in women. These deaths influence the next generation, and urgent action is needed to address unnecessary cancer deaths among women in Africa (4).

In 1991, Jensen and Whelan, in an International Agency for Research into Cancers (IARC) scientific publication, defined cancer registration as “the process of continuing, systematic collection of data on the occurrence and characteristics of reportable neoplasms with the purpose of helping to access and control the impact of malignancies on the community” (5). This statement still stands true and prompts discussion of how countries with no national cancer registry are to implement and monitor the progress or challenges of global cancer control programs like the Global Breast Cancer Initiative (GBCI) framework. National cancer registries tend to be more of a suggestion in global cancer control programs’ documents instead of a necessity to achieving cancer control in any country. Objective 6 of the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases acknowledges cancer disease registries and the importance of disease registries in understanding and monitoring of regional and national needs and implemented interventions (6). There is limited literature published about national cancer registries, their limited availability in LMICs, and the effects of the lack of national cancer registries on global cancer control programs, especially in LMICs. Particularly, there are alarming gaps in regard to the effective recommendations for setting up a national cancer registry in resource limited settings, standardized protocols for diagnosing breast cancer, guidance on integrating and controlling data sharing in such settings, and training materials on staff recruitment and data collection for operating cancer registries. LMICs are disproportionately affected by cancer mortality and the current figures are projected to increase exponentially over the next years from 520,348 in 2020 to about 1 million annually by 2030 (7).

Cancer control programs in countries like Ghana should be a public health concern and ought to follow the recommendations of the World Health Organization’s GBCI framework for reducing the annual mortality of breast cancer by 2.5% by 2040. To achieve this reduction in breast cancer cases, the GBCI highlights the pursuit of three pillars, described below:

Pillar 1: health promotion for early detection (pre-diagnostic interval)

In many LMICs, a vast majority of breast cancer diagnoses are made among women with visible breast changes, resulting in late-stage diagnoses such as locally advanced breast cancer (8). Early diagnosis programs are valued in such scenarios to aid in stage shifting, increasing the number of people diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, and improving the chances of disease survival over investing in breast cancer screening programs for the general population. Pillar I may be accomplished by countries that successfully diagnose 60% of invasive cancers at stage I or II.

Pillar 2: timely breast diagnosis (diagnostic interval)

Survival rates of breast cancer are dependent on the stage of diagnosis and the timing of treatment initiation. Decentralizing diagnostic services to include outreach to rural and minority communities in LMICs will be crucial, increasing the appeal of secondary level hospitals in providing diagnostic services over urban, tertiary level hospitals. Pillar II will be achieved by patients undergoing diagnostic evaluation, imaging, tissue sampling within 60 days of first presentation at a health center.

Pillar 3: comprehensive breast cancer management (treatment interval)

In LMICs, breast cancer treatment is delayed because of a myriad of reasons, including an exclusive focus on spiritual or herbal treatments, financial difficulties, unaffordable cancer care, or a lack of chemotherapy medications and surgical infrastructure in the country. To achieve this pillar, more than 80% of patients with a breast cancer diagnosis must complete multimodality treatment without attrition (9).

Much of the data points identified by the GBCI, particularly staging diagnoses and diagnosis to treatment intervals, may be found within cancer registries within countries. Yet discrepancies in data reporting exist. Some countries with national cancer registries have shown that their registry reports for the number of reported cancer cases differ from the official WHO’s Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) figures, from 5–10% in Bhutan, Indonesia, Iran, the Republic of Korea, Singapore and Thailand to more than 10% recorded in China, India, Malaysia, Mongolia and Sri Lanka (10).

In the context of West African countries, GLOBOCAN’s cancer incidences are drawn from a combination of data sources, including national cancer registries and hospital based registries; death registration systems in estimating mortality rates; population based surveys for information on demographics and risk factors for cancer development (11). From this information, GLOBOCAN employs Bayesian statistics, regression analysis, and age-period-cohort models to develop models that draw relationships between cancer rates and risk factors that apply to the entirety of a country. Lastly, GLOBOCAN adjusts for under-reporting of cancer cases in West African countries through correction factors and estimation of data completeness in each country (12). In spite of these thorough methods, there are limitations to their approach; the quality and availability of confirmed cancer cases varies widely across West Africa, from verified histopathological diagnoses to verbal autopsy reports by family members, affecting the accuracy of their estimates (11).

LMICs cannot rely on GLOBOCAN figures as a substitute for a national cancer registry, as the calculated figures may not reflect the true situation of cancers in the country considering the complex contextual factors of health systems in LMICs that affect access to cancer care in the country, in addition to the limited capacities of hospitals due to limited financial resources, the lack of universal health coverage, and the cultural beliefs and misconceptions towards cancer that prevent patients from seeking follow-up care (13). How can a country with limited resources and no national cancer registry realistically implement and measure the progress of the GBCI framework and other global cancer control program recommendations that have worked in high-income countries (HICs)? Indeed, all HICs with a decrease in breast cancer mortality, according to the GBCI framework, share a unifying commonality of having national cancer registries. This narrative review thus explores the following question: “How integral is the presence of a national cancer registry in implementing the GBCI framework?” We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://tbcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tbcr-24-60/rc).

Methods

This narrative review sought to evaluate the status of breast cancer registries in West Africa and evaluate their preparedness in achieving the GBCI framework set out by the WHO (Table 1). We searched for published literature in PubMed, international health websites, such as the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume XII website and GLOBOCAN 2022 Cancer Factsheet, African Cancer Registry Network (AFCRN), and world population data sources using our search keywords (Table 2) to identify the status and population coverage of cancer registries in 17 West African countries (1,14-16). Additionally, our search keywords were used to detail Ghana’s journey towards registry development as a descriptive case analysis of the barriers and facilitators of registry development within the region. The review protocol was not amended. The last review was performed in September 2024.

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | August 1, 2024 to September 7, 2024 |

| Databases and other sources searched | PubMed, international health and conference websites, Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume XIII, GLOBOCAN 2022 Cancer Factsheet |

| Search terms used | ‘Breast cancer’ AND ‘national cancer registry’ AND ‘Global Breast Cancer Initiative’ |

| Timeframe | No limit |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria: published research articles, reviews and documents discussing the state of national cancer registries in West Africa and their role in implementing and controlling breast cancer incidence and mortality |

| Exclusion criteria: published work that didn’t focus on the reality of national cancer registries and their effect on breast cancer control policy implementation were excluded | |

| Selection process | Reviewed literature was selected by A.O.A., and supplemented and reviewed by all the authors |

Table 2

| Country/region | Population | Cancer incidence source | Last documented date of registry update (AFCRN) | Population served by cancer registry | Percent coverage of population registry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | 12,784,728 | Sub-national (Cotonou and Parakou) | Cotonou: not documented | Cotonou: 708,999 | 5.55% |

| Parakou: 24 November 2024 | Parakou: 391,442 | 3.06% | |||

| Burkina Faso | 22,102,838 | Sub-national (Ouagadougou) | N/A (non-member) | 3,055,790 | 13.83% |

| Cape Verde | 567,676 | National | Not documented | 525,861 | 92.63% |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 27,742,301 | Sub-national (Abidjan) | Not documented | 5,515,790 | 19.88% |

| Ghana | 32,395,454 | Sub-national (Kumasi) | March 2017 | 3,630,330 | 11.21% |

| Guinea | 13,865,692 | Sub-national (Conakry) | Not documented | 2,048,520 | 14.77% |

| Guinea-Bissau | 2,063,361 | No data | – | – | |

| Liberia | 5,305,119 | No data | – | – | |

| Mali | 21,473,776 | Sub-national (Bamako) | Not documented | 2,816,940 | 13.12% |

| Mauritania | 4,901,979 | No data | – | – | |

| Niger | 26,083,660 | Sub-national (Niamey) | N/a (non-member) | 1,383,910 | 5.31% |

| Nigeria | 216,746,933 | Sub-national (Abuja municipal, Calabar and Ekiti) | Abuja: not documented | Abuja 3,652,030 | 1.68% |

| Calabar: 10 July 2019 | Calabar 630,628 | 0.29% | |||

| Ekiti: not documented | Ekiti 3,592,200 | 1.66% | |||

| Sao Tome and Principe | 227,679 | No data | – | – | |

| Senegal | 17,653,669 | No data | – | – | |

| Sierra Leone | 8,306,442 | No data | – | – | |

| The Republic of the Gambia | 2,558,493 | National | No (non–member) | 2,558,493 | 100% |

| Togo | 8,680,832 | No data | – | – | |

| West Africa | 423,460,632 | Population weighted average | Not available | 29,985,072 | 7.08% |

The data for this table were drawn from statistics and registry data on Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume XII website, GLOBOCAN 2022 cancer factsheet, AFCRN, and world population data sources (1,14-16). Note that the last documented date of registry update was determined by the last updated country webpage dates of countries part of the AFCRN. AFCRN, African Cancer Registry Network; GLOBOCAN, WHO’s Global Cancer Observatory.

Results

Breast cancer registry development in West Africa

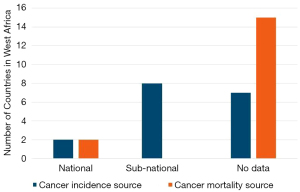

The only countries possessing a national registry in West Africa are Cape Verde and the Republic of Gambia (Figure 1 and Table 2). Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Niger, and Nigeria possess sub-national registries, namely hospital-based and population-based registries with minimal catchment areas focused solely on urban centers. In total, cancer registries in West Africa covered just 7.08% of the population. While the two documented national registries of Cape Verde and The Republic of Gambia covered 92.6% and 100% of their populations, respectively, sub-national registries covered between 0.29% (in the case of the Calabar sub-national registry in Nigeria) to 19.88% of the population (in the case of the Abidjan subnational registry in Cote d’Ivore), with the average sub-national registry covering 6.39% of a country’s population. Among the countries with multiple sub-national registries, such as Nigeria and Benin, there was no indication or measurement of duplicate cancer cases recorded between registries.

Additional data quality findings from the literature search revealed that among the countries included within the AFCRN regional registry collective, only one registry, Benin’s Parakou registry, has up to date cancer registry data from the past year on the AFCRN website (16). Furthermore, the Cotonou population-based registry in Benin is the only registry in West Africa accepted into the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume XII Report due to its meeting of WHO data quality standards for cancer registry data (14).

Ghana’s journey to establishing a national cancer registry

Ghana is a country in West Africa with a population of 32.4 million (1). There is no national cancer registry in Ghana and only one sub-national cancer registry. The Kumasi cancer registry (KsCR) is listed as a source for cancer incidence in the 2022 GLOBOCAN report, with no data source for cancer mortality in the country (1,17).

On March 1, 2012, the AFCRN was formally recognized as a capacity building regional collective for providing technical support and staff training for evaluating cancer registry data, while advocating for the need to establish high quality cancer registries. The network offers membership to population-based registries in Africa that meet several data quality requirements, including: (I) initial coverage of over 50% of the target catchment area (often a city, district, or region) of a registry, and (II) passing an AFCRN consultant evaluation visit of the cancer registry. There are 30 AFCRN members from 19 countries and 18 countries still have no data available (18). The KsCR is listed as a member of AFCRN (16).

In LMICs with no national cancer registry, data from hospital-based cancer registries can sometimes be collated to serve as the bases for population-based cancer registries (PBCRs) especially when there is no core difference in the data caption area and type of data being recorded in these two types of cancer registries. The KsCR is not representative of the full picture of cancer incidence and mortality in Ghana because there are key differences in cancer incidence and survival across the different regions and the KsCR only covers the population of the Kumasi region.

The idea of a national cancer registry for a fuller representation of cancer coverage in Ghana was first mentioned in Ghana in the early 1970s, yet there is still no functioning national cancer registry in Ghana. In the 2012–2016 national strategy for cancer control in Ghana, 2 hospital-based cancer registries are listed: Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH) registry in Accra [the foundation of the Accra Cancer Registry (ACR)], and Komfo-Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) registry in Kumasi (the foundation of the KsCR). The need for a national cancer registry with 7 main objectives is highlighted in this document with 5,820,000 USD as the predicted 4-year budget for this project (19). In 2001, the IARC collaborated with the Non Communicable Disease division of the Ministry of Health in Ghana to expand the KBTH registry in Accra into a PBCR (the ACR), which ended unsuccessfully. In 2011, a second attempt was made to develop the ACR but once again failed. Currently, there are efforts underway to try re-establishing the ACR, with the goal of having it become the foundation for a national cancer registry in Ghana where national data will be collated (20). Attempts to convert a hospital-based registry into a population-based registry were more successful in Kumasi, where the KATH hospital registry evolved into the KsCR registry, a PBCR which, as discussed, still remains in the country today (21). To date, the KsCR registry is the only functioning PBCR in Ghana.

The KsCR in Ghana has made significant strides in improving cancer data collection and management. One of its major strengths is the implementation of robust confidentiality practices to ensure the safety of patient data (22). This includes signing confidentiality agreements, restricting access to authorized personnel, and using password-protected software. The registry has also expanded its data collection to include information from various hospitals, pathology laboratories, and birth and death registries, which has improved the quality of data collected on patients diagnosed with cancer in Ghana (21). The registry’s transition from paper to electronic data collection using the IACR’s CanReg5 software has also transformed the landscape of retrieving, storing, and verifying cancer cases in Kumasi (22). Lastly, the registry has established sustainable partnerships with various international stakeholders, including the City Cancer Challenge Foundation in Geneva, to receive sustainable funding in maintaining data collection operations and engage in capacity building around data analysis (23,24).

Discussion

Lessons learned from the KsCR registry in Ghana

The KsCR demonstrates that establishing more PBCRs in Ghana is feasible and necessary to strengthen public health surveillance, improve cancer data quality, and enhance national efforts in cancer prevention and control (25). Among the factors that have made the Kumasi Registry successful as a cancer registry within a low-resource setting, include: (I) its use of an electronic data collection system, particularly the IACR’s CanReg5 software, (II) sustainable funding partnerships with international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and (III) use of histopathological verification in officially confirming cancer cases.

Notably, the KsCR membership in the AFCRN has demonstrated the utility of regional cancer registry bodies in enhancing data quality, target population coverage, capacity building, and overall performance of PBCR. Through providing standardized data collection tools and data validation protocols, the AFCRN has ensured consistency and accuracy in data collection for KsCR (16). Additionally, with the AFCRN’s support, the KsCR has successfully expanded its target population coverage to capture cancer data from a larger geographic area. AFCRN-guided training seminars have further improved the ability of data operators to analyze the data collected from the KsCR registry and also importantly guided the developers of KsCR in disseminating the results of the registry to international stakeholders, local policymakers, and civil society, raising the KsCR’s visibility, both domestically and abroad.

The main challenges the registry presently experiences, emblematic of the challenges experienced across all of West African registries, is maintaining and publishing up to date information on new cancer cases. Indeed, the outdated information on cancer cases documented by West African cancer registries on the AFCRN website reflects the difficulty in continuing registration activities after the initial inception period of registries. In addition to maintaining data collection operations, it is also crucial that cancer registries in West Africa expand their data catchment areas to include rural communities, allowing for greater coverage of the population beyond the average 7.01% national coverage reflected across country registries (Table 2).

Limitations of national cancer registries

While the establishment of national cancer registries provides a vehicle for achieving the GBCI framework, we acknowledge that not all key performance indicators can be achieved through use of cancer registries alone. Indeed, even among the high-quality cancer registries, such as those included in the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents report, the routinely collected registry data may only include information on breast cancer screening (KPI I) and histopathological diagnosis and verification (KPI II) (6,14). The most well-established cancer registries continue to face barriers in tracking the follow up status of patients officially diagnosed with cancer, making treatment initiation and follow-through (KPI III) challenging pieces of data for cancer registries to collect and monitor. We therefore acknowledge that to truly achieve all KPI indicators of the GBCI framework, the creation of high-quality, routinely-collecting registries must be complemented by policy interventions that deliver treatments to patients diagnosed with cancer and mobilize hospitals and other health care facilities in monitoring these patients as they engage with the health care system in seeking treatment follow-through.

Conclusions

A national goal within the countries of West Africa, including Ghana, is needed to set up an automated system for standardized data collection and integrate standardized population-based cancer data into a national cancer registry. The operations and data collection systems of all sub-national registries should be harmonized and standardized to aid the seamless and effective data aggregation and analysis. A national cancer registry is the only way to access quality and reliable data about the state of cancer incidence and mortality in each country. Indeed, all HICs listed in GBCI for achieving a >2% annual reduction in their breast cancer mortality rate have functional national cancer registries. We need more information on the role of national cancer registries in implementing the GBCI framework in LMICs and monitoring LMIC performance in achieving GBCI pillars. Based on these findings, we ought to consider making national cancer registries a first step requisite for LMICs endeavoring to implement the GBCI framework to ultimately reduce breast cancer mortality.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Global Health Catalyst Summit for bringing the authors of this paper together to discuss their shared interest in cancer registry development within LMICs.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://tbcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tbcr-24-60/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tbcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tbcr-24-60/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tbcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tbcr-24-60/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2022: Population fact sheets [Internet]. Lyon: IARC; 2022 [cited 2024 Sep 7]. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en/fact-sheets-populations#regions

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2022: Population Africa fact sheets [Internet]. Lyon: IARC; 2022 [cited 2024 Aug 1]. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/903-africa-fact-sheet.pdf

- Guida F, Kidman R, Ferlay J, et al. Global and regional estimates of orphans attributed to maternal cancer mortality in 2020. Nat Med 2022;28:2563-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galukande M, Schüz J, Anderson BO, et al. Maternally Orphaned Children and Intergenerational Concerns Associated With Breast Cancer Deaths Among Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:285-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jensen OM, Whelan S. Planning a cancer registry. IARC Sci Publ 1991;22-8. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases 2013-2020. Geneva: WHO; 2013:28-9.

- Ngwa W, Addai BW, Adewole I, et al. Cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:e251-312. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jedy-Agba E, McCormack V, Adebamowo C, et al. Stage at diagnosis of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e923-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global breast cancer initiative implementation framework: assessing, strengthening and scaling up of services for the early detection and management of breast cancer: Executive summary. Geneva: WHO; 2023.

- Ong SK, Haruyama R, Yip CH, et al. Feasibility of monitoring Global Breast Cancer Initiative Framework key performance indicators in 21 Asian National Cancer Centers Alliance member countries. EClinicalMedicine 2023;67:102365. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Data sources and methods by country [Internet]. Lyon: IARC; [cited 2024 Sep 7]. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en/data-sources-methods-by-country-detailed

- Ayandipo O, Wone I, Kenu E, et al. Cancer ecosystem assessment in West Africa: health systems gaps to prevent and control cancers in three countries: Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal. Pan Afr Med J 2020;35:90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clegg-Lamptey J, Dakubo J, Attobra YN. Why do breast cancer patients report late or abscond during treatment in ghana? A pilot study. Ghana Med J 2009;43:127-31. [PubMed]

- Bray F, Colombet M, Aitken JF, et al. editors. Cancer incidence in five continents, Vol. XII (IARC CancerBase No. 19). Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2023.

- World Population Review. Cities by population [Internet]. World Population Review; [cited 2025 Feb 16]. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities

- African Cancer Registry Network. AFCRN aims to improve the quality of population-based cancer registration in sub-Saharan Africa [Internet]. Available online: https://afcrn.org/#:~:text=AFCRN%20aims%20to%20improve%20the,the%20identification%20of%20problems%2C%20priorities

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:7-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Initiative for Cancer Registry Development (GICR) [Internet]. Available online: https://gicr.iarc.fr/hub/sub-saharan-africa/ [cited 2024 Aug 10].

- Ministry of Health, Ghana. Chapter 8 – Cancer registry and research. National strategy for cancer control in Ghana 2012-2016. Accra: Ministry of Health; 2011:44-50.

- Yarney J, Ohene Oti NO, Calys-Tagoe BNL, et al. Establishing a Cancer Registry in a Resource-Constrained Region: Process Experience From Ghana. JCO Glob Oncol 2020;6:610-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Brien KS, Soliman AS, Awuah B, et al. Establishing effective registration systems in resource-limited settings: cancer registration in Kumasi, Ghana. J Registry Manag 2013;40:70-7. [PubMed]

- Laryea DO, Awittor FK. Ensuring confidentiality and safety of cancer registry data in Kumasi, Ghana. Online J Public Health Inform 2017;9:e130. [Crossref]

- City Cancer Challenge. Kumasi marks major milestone in addressing cancer data challenge with relaunch of cancer registry [Internet]. Geneva: City Cancer Challenge; [cited 2025 Feb 16]. Available online: https://citycancerchallenge.org/kumasi-marks-major-milestone-in-addressing-cancer-data-challenge-with-relaunch-of-cancer-registry/

- City Cancer Challenge. Kumasi [Internet]. Geneva: City Cancer Challenge; [cited 2025 Feb 16]. Available online: https://citycancerchallenge.org/city/kumasi/

- Laryea DO, Awuah B, Amoako YA, et al. Cancer incidence in Ghana, 2012: evidence from a population-based cancer registry. BMC Cancer 2014;14:362. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Nair S, Ngwa W, Addai BW, Addai AO, Oti BA. The role of a national cancer registry in effective implementation and monitoring of the Global Breast Cancer Initiative (GBCI) framework in Ghana: a narrative review. Transl Breast Cancer Res 2025;6:20.